What is an FMEA?

Also called: potential failure modes and effects analysis; failure modes, effects, and criticality analysis (FMECA)

- "Failure modes" means the ways, or modes, in which something might fail. Failures are any errors or defects, especially ones that affect the customer and can be potential or actual.

- "Effects analysis" refers to studying the consequences of those failures.

When to Use FMEA?

- When a process, product, or service is being designed or redesigned, after deployment.

- When an existing process, product, or service is being applied in a new way.

- Before developing control plans for a new or modified process.

- When improvement goals are planned for an existing process, product, or service.

- When analyzing failures of an existing process, product, or service.

- Periodically throughout the life of the process, product, or service.

Process

- Assemble a cross-functional team of people with diverse knowledge about the process, product or service, and customer needs.

- Identify the scope of the FMEA.

- "Is it for the concept, system, design, process, or service?"

- "What are the boundaries?"

- "How detailed should we be?"

- Use flowcharts to identify the scope and to make sure everybody understands it in detail.

- Fill in the identifying information at the top of your FMEA form.

- The remaining steps ask for information that will go into the columns of the form.

- Identify the functions of your scope. Ask:

- "What is the purpose of this system, design, process, or service?"

- "What do our customers expect it to do?"

- Name it with a verb followed by a noun. Usually, one will break the scope into separate subsystems, items, parts, assemblies, or process steps and identify the function of each.

- For each function, identify all the ways failure could happen.

- These are potential failure modes. If necessary, go back and rewrite the function with more detail to be sure the failure modes show a loss of that function.

- For each failure mode, identify all the consequences on the system, related systems, process, related processes, product, service, customer, or regulations.

- These are potential effects of failure. Ask,

- "What does the customer experience because of this failure?"

- "What happens when this failure occurs?"

- Determine how serious each effect is.

- This is the severity rating or S. Severity is usually rated on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 is insignificant and 10 is catastrophic.

- If a failure mode has more than one effect, write on the FMEA table only the highest severity rating for that failure mode.

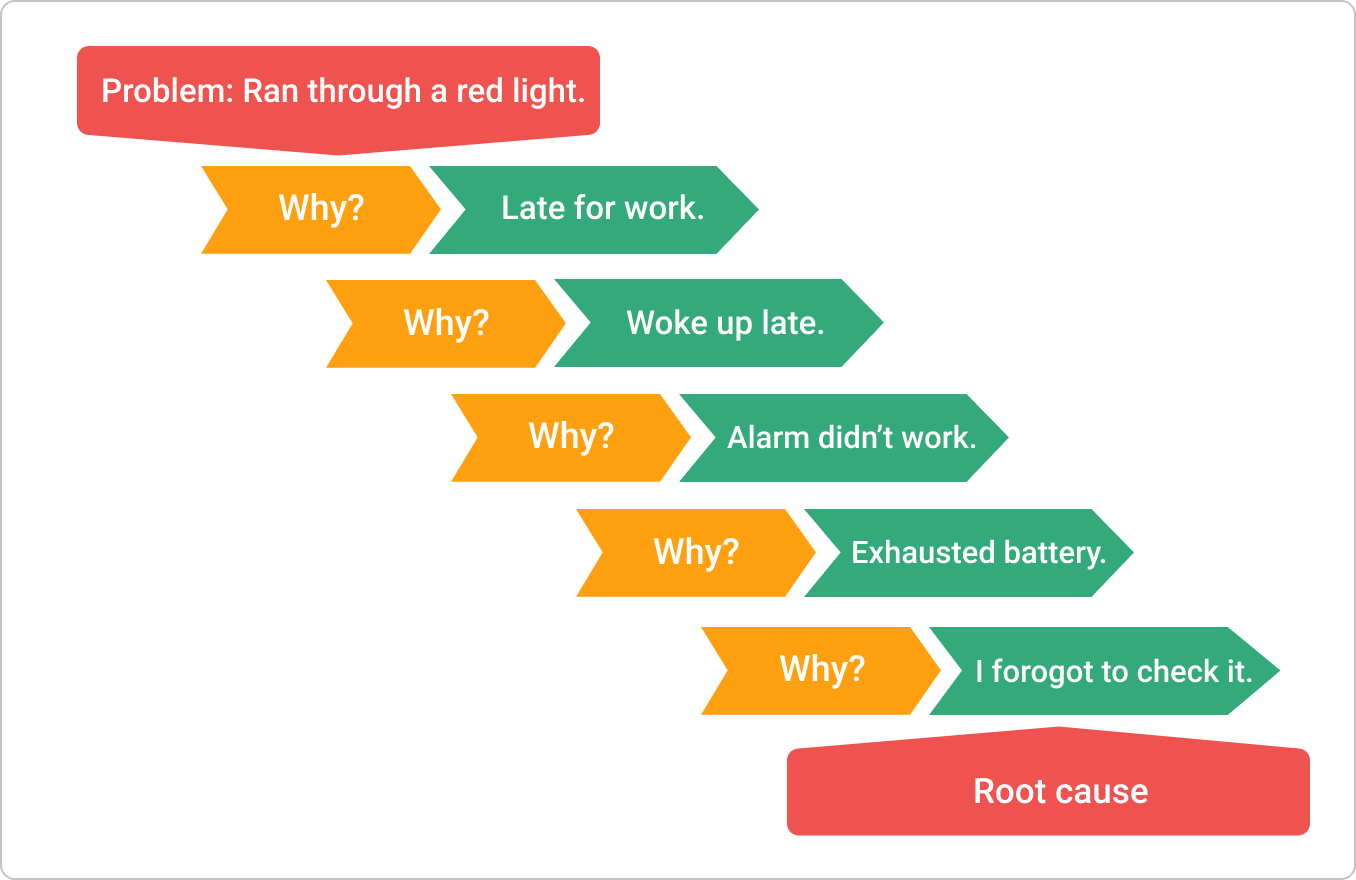

- For each failure mode, determine all the potential root causes.

- Use tools classified as cause analysis tools, as well as the best knowledge and experience of the team.

- List all possible causes for each failure mode on the FMEA form.

- For each cause, determine the occurrence rating, or O.

- This rating estimates the probability of failure occurring for that reason during the lifetime of your scope.

- Occurrence is usually rated on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 is extremely unlikely and 10 is inevitable.

- On the FMEA table, list the occurrence rating for each cause.

- For each cause, identify current process controls.

- These are tests, procedures, or mechanisms that you now have in place to keep failures from reaching the customer.

- These controls might prevent the cause from happening, reduce the likelihood that it will happen, or detect failure after the cause has already happened but before the customer is affected.

- For each control, determine the detection rating, or D.

- This rating estimates how well the controls can detect either the cause or its failure mode after they have happened but before the customer is affected.

- Detection is usually rated on a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means the control is absolutely certain to detect the problem and 10 means the control is certain not to detect the problem (or no control exists).

- On the FMEA table, list the detection rating for each cause.

- Optional for most industries: Ask

- "Is this failure mode associated with a critical characteristic?" (Critical characteristics are measurements or indicators that reflect safety or compliance with government regulations and need special controls.)

- If so, a column labeled "Classification" receives a Y or N to show whether special controls are needed. Usually, critical characteristics have a severity of 9 or 10 and occurrence and detection ratings above 3.

- Calculate the risk priority number, or RPN, which equals S × O × D.

- Also calculate Criticality by multiplying severity by occurrence, S × O.

- These numbers provide guidance for ranking potential failures in the order they should be addressed.

- Identify recommended actions.

- These actions may be design or process changes to lower severity or occurrence.

- They may be additional controls to improve detection.

- Note who is responsible for the actions and target completion dates.

- As actions are completed, note the results and the date on the FMEA form.

- Note new S, O, or D ratings and new RPNs.

Notes

- This is a general procedure.

- Specific details may vary with the standards of your organization or industry.

- Before undertaking an FMEA process, learn more about standards and specific methods in your organization and industry through other references and training.

.png)

.png)