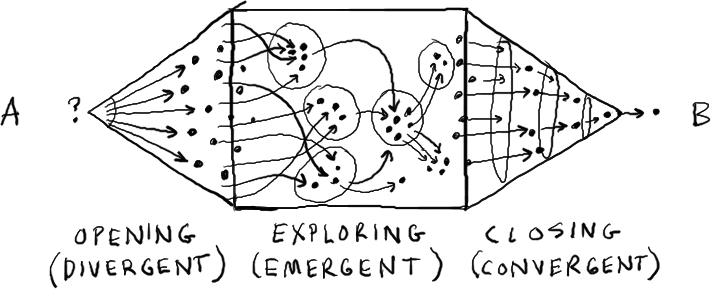

The overall goal of a project may take several meetings to achieve. Each meeting can be seen in its own terms, a context within which the group can progress towards the overall goal by achieving two or three narrow meeting goals.

Meetings goals are specific, well-defined, and realistic designed to be achieved in the time frame of a single meeting. There are seven types of meeting goals.

Meeting Goal 1 - Share Information

- Meeting planners who understand this can build in opportunities, like quick conversations in pairs, for members to digest what they are hearing, so they can apply it when and how they need to.

- A typical string of activities:

- Activity 1 - Presentation.

- Activity 2 - Pairs

- Activity 3 - Questions/Structure Go-around/Individual writing.

- Outcome: The information is digested.

Meeting Goal 2 - Provide Input

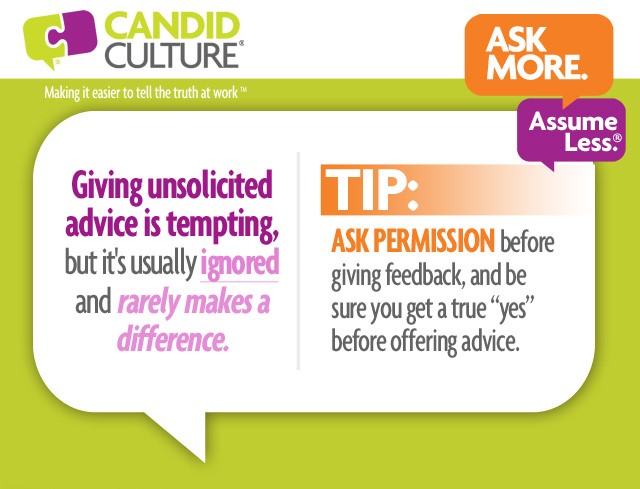

- When participants realize they are asked for just input then they can focus on influencing the presenter and not the other meeting participants.

- When participants mistakenly think they are invited to decision-making, they put the effort into critiquing and debating with the hope of creating support for their ideas, and often become frustrated and demoralized.

Meeting Goal 3- Advanced Thinking

- Meeting planners can become more precise in setting realistic and useful meeting objectives.

- The group members must understand the objective clearly to think and not mistake the goal.

- Example: Define the Problem, Analyze the Problem, Identify Root Causes, Identify...

Meeting Goal 4 - Make Decisions

- What is the decision rule we will use to take the decision?

- People who have to decide on tough issues are more likely to feel compelled to build a shared understanding of the complexity involved.

Meeting Goal 5 - Improve Team Communication

- Take the group members from their task-related issues, to talk instead about their feelings and their relationships with one another.

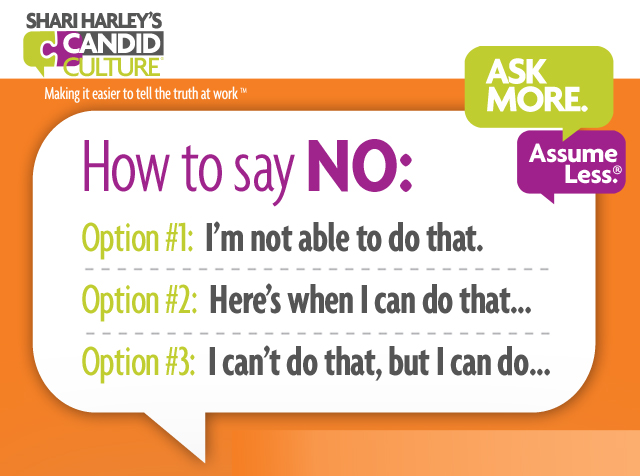

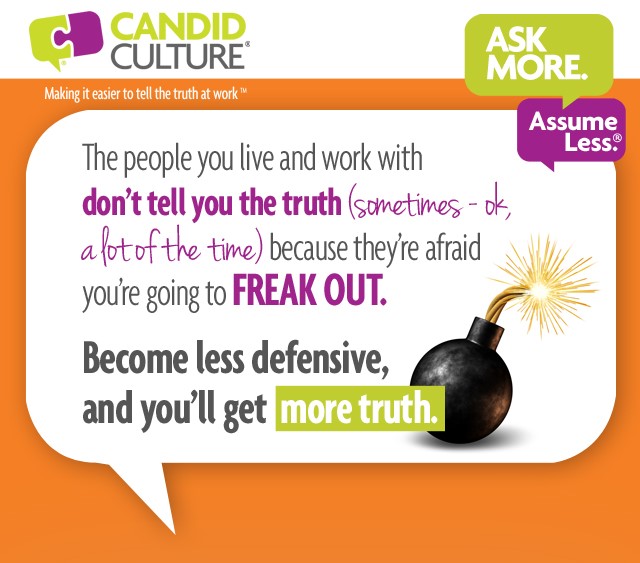

- It takes a skillful, well-planned approach - first to create a safe, supportive foundation, and then gently nurture self-disclosure and interpersonal feedback.

Meeting Goal 6 - Build Team Capacity

- Some examples are problem-solving, decision-making, increase knowledge of major trends in the team's industry, and acquisition of methods, or best practices.

Meeting Goal 7 - Build Community

- Time achievements and life events (like birthdays) can take place within 5-10 minutes.

- Volunteer as a group, share reactions to momentous current events, and do simple creative energizers.